1. Background

This consensus document, coordinated by the AIDS Study Group of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC-GeSIDA) and the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine (semFYC), arises from the need to pool knowledge and evidence to improve the multidisciplinary and coordinated approach between Primary Care (PC) and Hospital Care (HC), both in the prevention and screening of HIV infection in the general population, and in the comprehensive care of the multiple aspects and nuances that make up the care of people living with HIV (PLHIV)1.

The recommendations of the four blocks, which contemplate bidirectionality and communication between the two care settings, are summarized here. Some recommendations may have been updated after the publication of the original consensus document; the clinical guidelines published periodically by GeSIDA should be consulted.

2. Prevention, diagnosis, and referral

2.1 Prevention of HIV infection

The starting point for preventing HIV infection is identifying the risk of acquisition to apply the most appropriate prevention measures for each individual (A-II).

How can we improve risk identification?

- We need to raise awareness about screening guidelines that identify persons at increased risk of acquiring HIV infection (A-II).

- Patient medical histories should include the number of sexual partners, types of practices, condom use, drug use during sexual intercourse, sharing of drug-related material during consumption, history of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), psychosocial situation, and country of origin. Staff should be given sufficient time to attend to each patient according to their needs (B-III).

What are the non-pharmacological prevention measures for HIV and other STIs?

- Gynecological prevention and family planning (B-III). Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (A-I).

- Male circumcision only in settings with generalized/widespread HIV epidemic (C-II).

- Condom use (A-II)

- Regular HIV testing in populations at high risk (A-III)

- Behavioral modification interventions (informational campaigns, sex education, outreach to vulnerable people, risk reduction...) (B-II)

- Social assessment, including socio-familial environment and livelihoods, to provide support measures if necessary (B-II)

- Syphilis screening annually if there is unprotected sex (B-II), and in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) with risk factors, monitoring at least N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis and hepatitis C virus (C-II). Screening should be performed every 3-6 months, depending on risk factors.

What are the pharmacological HIV prevention measures?

- Offer antiretroviral treatment (ART) to all PLWH (A-I), according to current recommendations in clinical guidelines2.

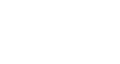

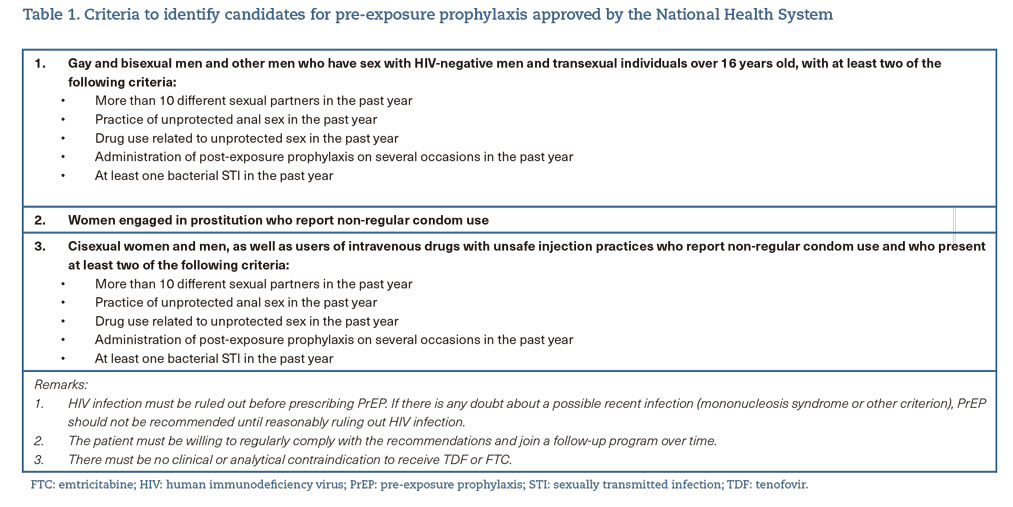

- Offer pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (A-I) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) (A-II) in situations in which they are indicated, following current recommendations3 (table 1 and 2).

- Regular screening and early treatment of STIs, since ulcerative and rectal STIs increase the risk of acquiring HIV (B-II).

2.2 Diagnostic delay. Strategies to optimize screening

What do the clinical guidelines recommend?

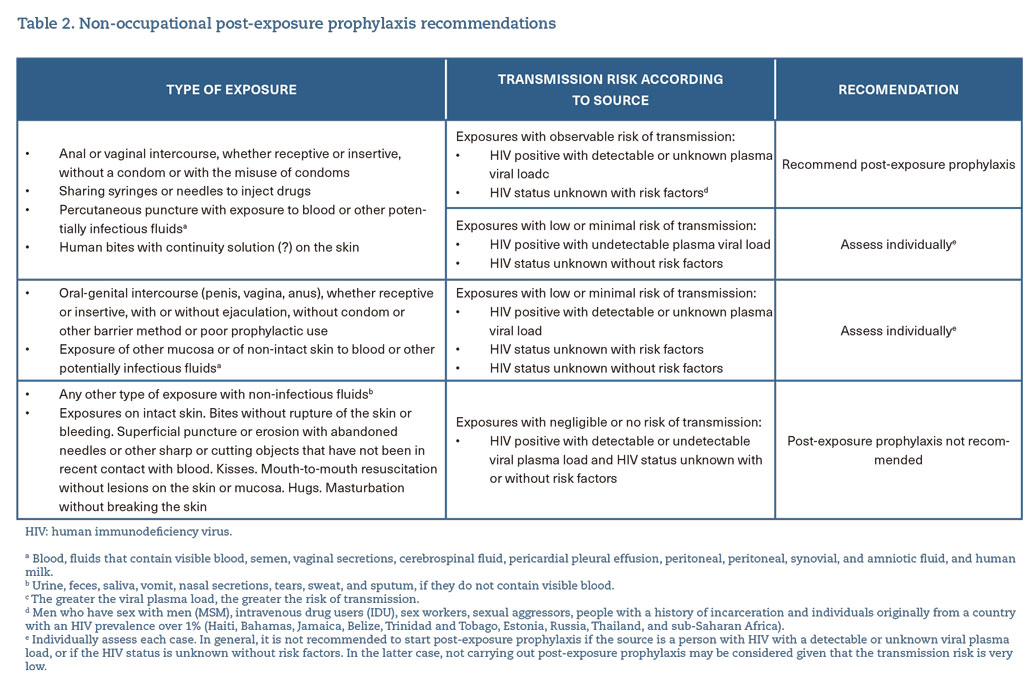

- The guidelines propose different screening recommendations, from the routine offer to the general population to the targeted offer for people at higher risk5,6.

- In Spain, there is a Guide of Recommendations for the Early Diagnosis of HIV in healthcare settings7 (figure 1), which should be updated according to the latest available evidence (A-II).

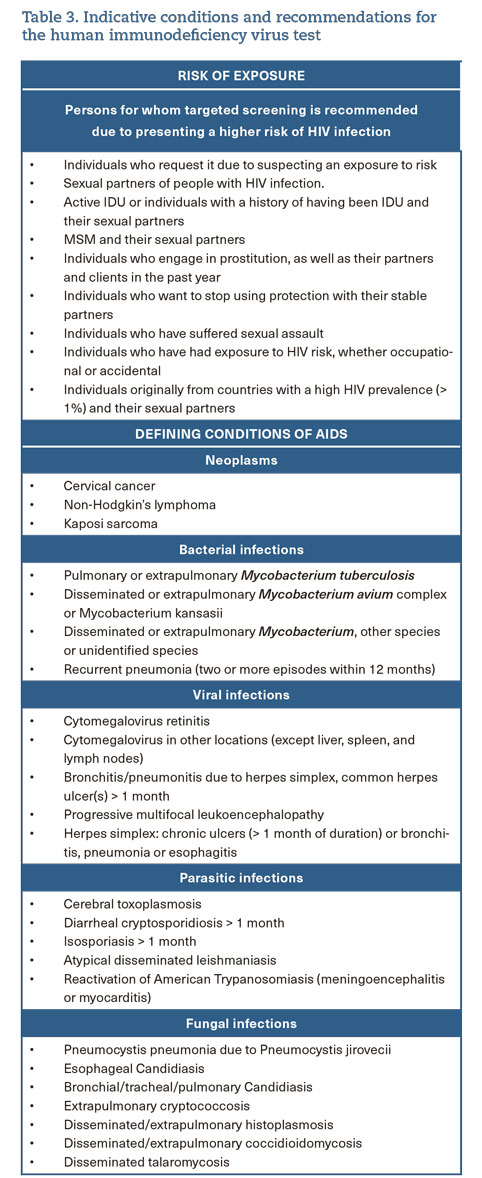

- The training of healthcare professionals on the implications of diagnostic delay should be reinforced so that they request HIV testing more frequently (A-III) (table 3).

- Strategies should be implemented to carry out screening in different healthcare settings, providing professionals with the appropriate working conditions in order to perform them (A-II).

What are the practical experiences in our setting?

- In Spain, we have extensive practical experience in strategies to optimize HIV screening, both in healthcare and community settings, including mobile units, pharmacies, premises managed by NGOs, and outreach strategies in high-risk environments with offers in leisure or street venues8-15.

- We especially recommend optimizing screening by implementing strategies in PC and community settings (B-I).

2.3 Referral to Hospital Units

- Referral for ART is recommended for all patients with HIV infection (A-I) as soon as possible after diagnosis (A-II).

- Dynamic communication should be facilitated between primary care specialists and hospitalists to enable patient access in any situation that may require it. Non-face-to-face referrals or e-consultations should be optimized to avoid excesses/mistakes in referrals and to guarantee the rapid exchange of information (A-II).

- Rapid two-way inter-consultation circuits should be generated between PC and HC for PLWH presenting STIs, infections not associated with HIV, the need to study a systemic syndrome or for those who cannot go to the hospital and can be attended in PC, as well as displaced patients who need to carry out specific administrative procedures (A-III).

- PLWH should be referred to PC if they require care for healthcare matters usually managed by the family physician, keeping the latter at the center of the care of PLWH (A-II).

3. Shared care for people living with HIV

3.1 Coordination and Quality of Care

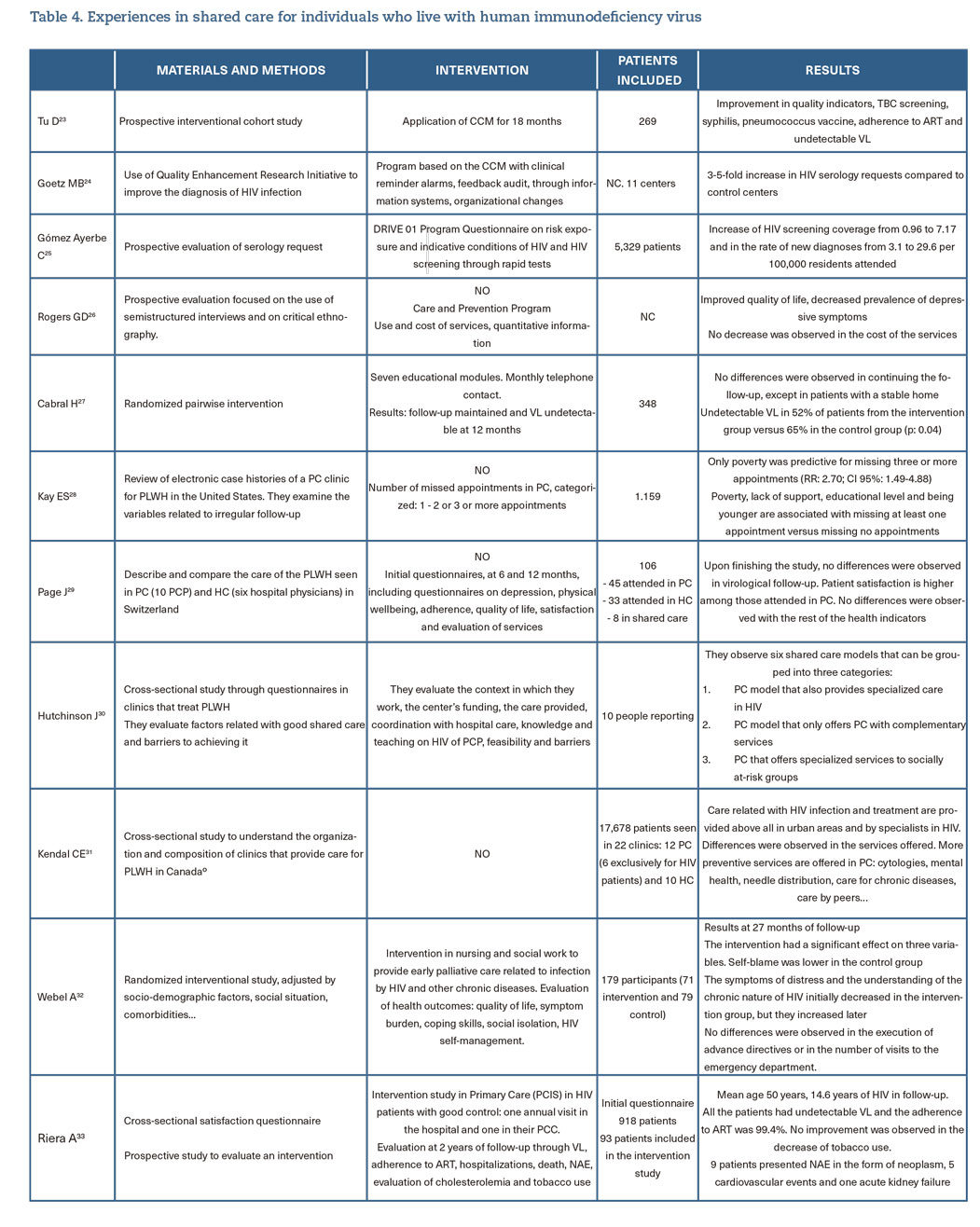

Shared care combines the advantages of PC (proximity and expertise in chronic diseases) with the expertise of an HIV specialist. Although the WHO has recommended shared care since 2004, scarce data are available that evaluate these models in high-income countries, with generally good health outcomes (table 4).

What are the main recommendations for shared care?

- Using all care settings to support early diagnosis, counseling, and shared follow-up of PLWH is recommended (B-III).

- Generating evidence on shared care in high-income countries is considered a priority (C-III).

- With the increase in age and comorbidities in PLWH, it is necessary to implement effective organizational models in other chronic diseases, which implies improving coordination between HC and PC (A-III).

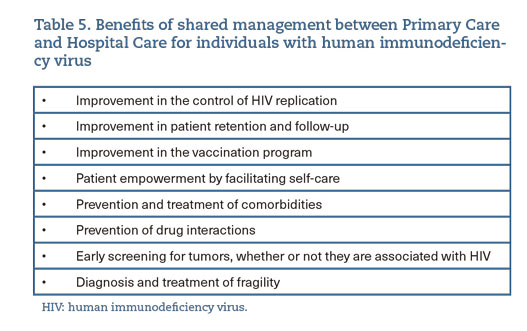

- A chronic and shared care model between PC and HC for PLWH should be implemented as soon as possible, which would greatly benefit both the patient and the healthcare system (B-II) (table 5).

New models of non-face-to-face care and coordination

- The national medical societies in Spain have guidelines regarding telemedicine in the management of PLWH16,17.

- Models of non-face-to-face care with patients and between HC and PC should be established to achieve greater proximity and accessibility of care (C-III).

- Telemedicine should be seen as a complementary support tool to optimize resources and facilitate patient care (C-III).

- Progress should be made towards safer and more standardized telemedicine care, and its results on the health of PLWH should be evaluated (C-III).

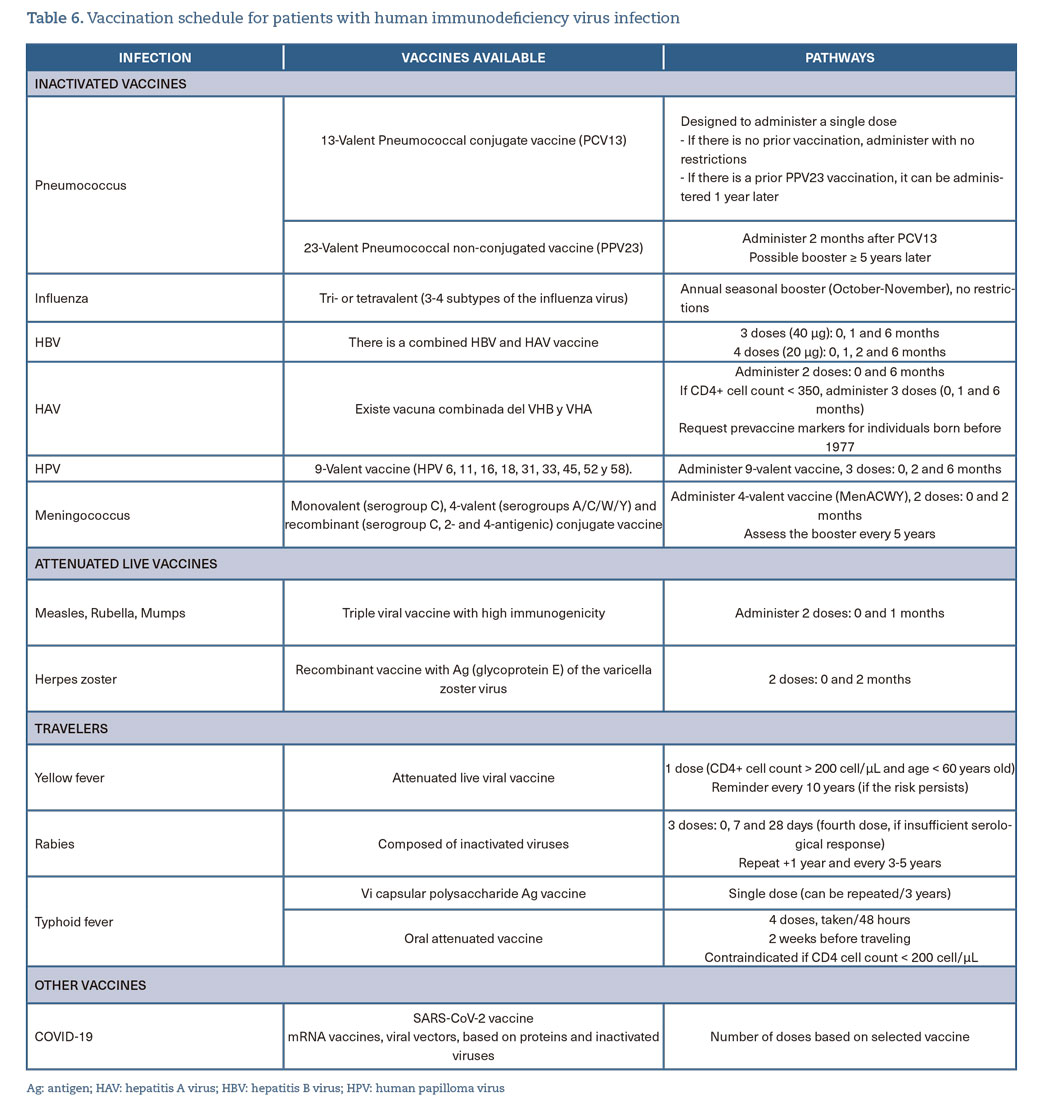

3.2 Vaccinations for patients with HIV infection

What are the recommendations on the vaccination schedule?

- Vaccinate with the same guidelines as the general population. Live attenuated vaccines with CD4+ cell counts < 200 cells/μL (A-I) are contraindicated.

- Pneumococcal (A-II), annual influenza (A-II), SARS-CoV-2 (A-II), high-dose HBV (A-I), and postvaccination serological response (B-I), hepatitis A (A-I), human papillomavirus (A-III), and herpes zoster (B-I) vaccines are indicated (table 6).

- Serology against the hepatitis A and B viruses should be performed on all patients at the beginning of the study to assess their vaccination status (A-I). In women of childbearing age, rubella serology is recommended for vaccination if IgG is negative (C-III).

- The vaccination status and the vaccination record should be reviewed both in PC and in HC (C-III).

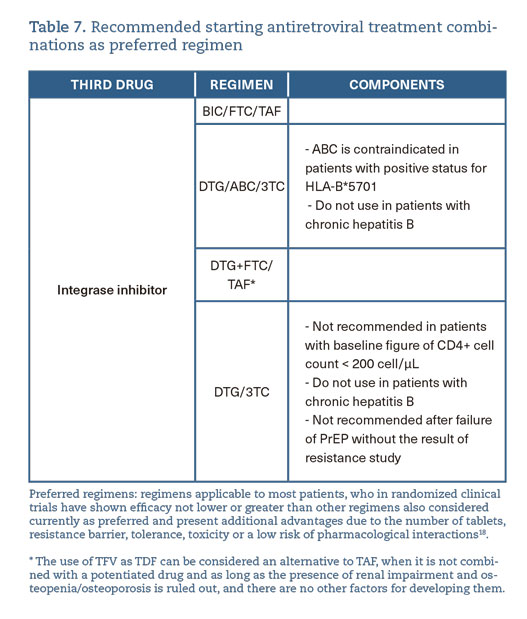

3.3 Current Antiretroviral Treatment Management

What are the recommendations for ART monitoring?

- ART consists of a combination of two or three antiretroviral drugs. Laboratory evaluation and aspects related to the choice and monitoring of ART are specified in the corresponding GeSIDA guidelines (table 7).

- It is essential to know the main side effects of antiretroviral drugs and to avoid polypharmacy, interactions, and new side effects (A-I).

- Special situations, such as pregnancy, tuberculosis, and/or comorbidities, require extreme precautions in monitoring and treatment (A-I).

How to manage interactions and polypharmacy?

- Collaboration between PC and HC professionals is critical in order to avoid severe interactions and to reduce the risk of polypharmacy (B-III).

- ART and concomitant medication should be accessible to all prescribing physicians in real-time (B-II).

- All medication for PLWH should be reviewed at every clinical visit, especially if the medication is to be modified. Online tools like the one developed by the University of Liverpool (available at: https://www.hiv-druginteractions.org/) can be used to assess interactions. Contraindications should be considered, and dose adjustments made when necessary (A-II).

How to monitor adherence and control ART?

- Adherence to ART should be monitored at each clinical visit. This should be done through multidisciplinary collaboration between healthcare professionals (A-II).

- Adherence to ART should be recorded in the clinical history. This information should be shared between PC and HC (C-III).

- The use of two independent methods for measuring adherence is recommended. Pharmacy records and simple validated questionnaires are easily accessible in the clinic (C-III).

- Healthcare for PLWH should include implementing adherence improvement programs, such as sending reminders via mobile devices or patient education programs (B-I).

3.4 Management of comorbidities

Cardiovascular risk

- Cardiovascular risk (CVR) should be assessed in the initial evaluation and repeated annually with any of the available tools (Framingham, REGICOR, D:A:D, ACC/AHC...) (A-I).

- Patients should be encouraged to change their lifestyle, including avoiding smoking (the main modifiable CVR factor), adopting a diet more suited to their needs, and providing the necessary physical exercise (A-II).

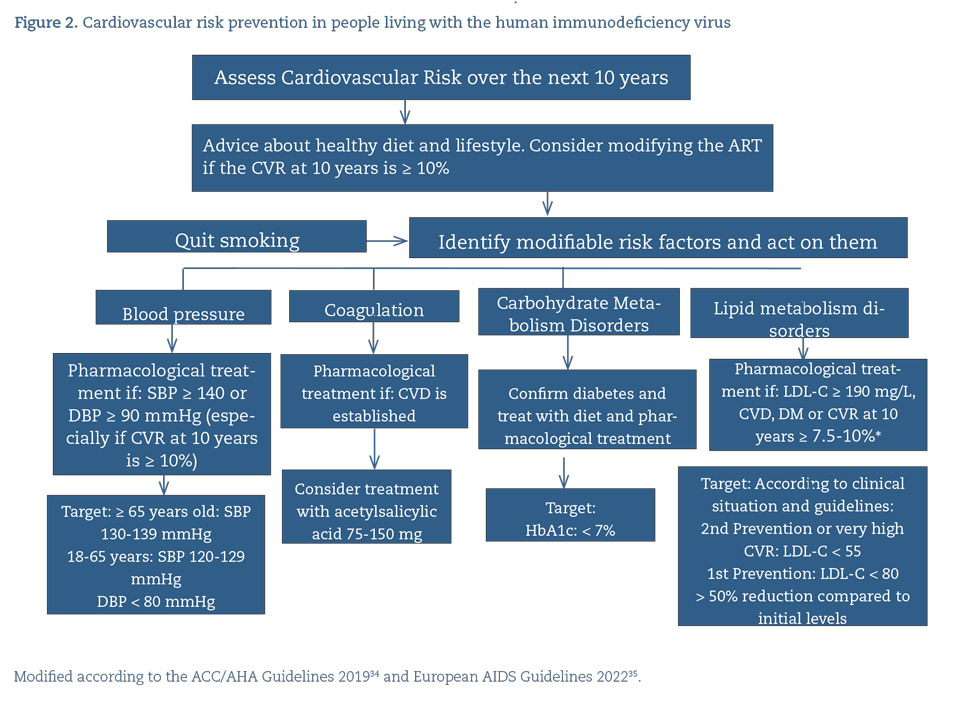

- In managing dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and high blood pressure, using the same therapeutic algorithm as in the general population is recommended, while taking interactions with ART into account (A-II) (figure 2).

- HbA1c should be requested before starting ART. Subsequently, in patients with diabetes, it should be monitored every six months to maintain a level < 7% (A-I).

- Interactions between the drugs used (mainly statins) and some antiretroviral drugs should be considered (A-II).

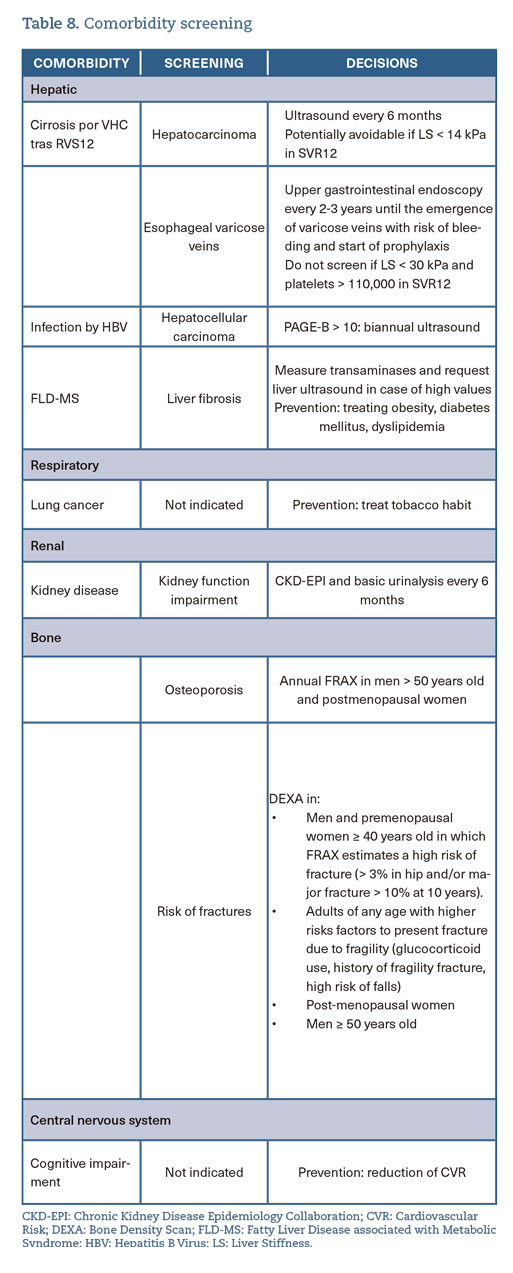

Hepatic, respiratory, renal, bone, and CNS comorbidities

- In patients with HIV infection, all hepatic, renal, bone, pulmonary, and/or CNS comorbidities should be evaluated at each clinical visit (HC and PC). Preventive screening and, if necessary, modification of lifestyle habits, antiretroviral therapy, and specific treatment of the healthcare issue should be performed (A-I) (table 8).

HIV-associated infections

- Knowing the vaccination status, the patient’s immunological status, and the use of prophylaxis for opportunistic diseases will help to establish an appropriate differential diagnosis for an infectious condition (A-II). The GeSIDA document on the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections and other coinfections in PLWH has recently been updated.

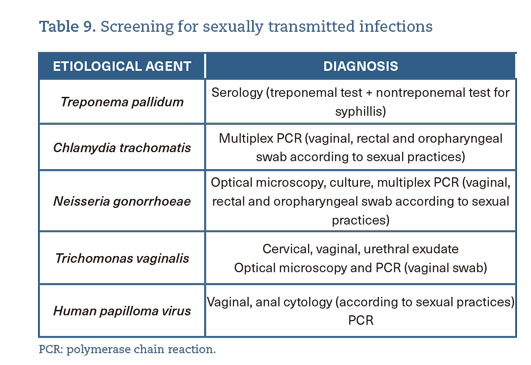

- Perform STI screening in sexually active patients at least once a year (or more frequently, depending on individual risk assessment) (A-II) (table 9).

- Active search for parasitosis in patients from specific countries (migrants, travelers...) (A-II).

Screening for neoplasms

- In the first year after the diagnosis of HIV infection, it is recommended to perform two cervical cytology tests (every six months). If both are normal, they should be repeated annually, including the inspection of the anus, vulva, and vagina (B-III).

- Breast and colon cancer screening should be performed according to the recommendations for the general population (B-III).

- In immunosuppressed patients (B-III):

- Annual cytology starting at age 21.

- From age 30:

- Triennial co-test in women with CD4 count > 200 cells/μl and active ART.

- Annual co-test with CD4 count < 200 cells/μl or without ART (B-III).

- Currently, anal cytology, followed by high-resolution anoscopy if the cytology is abnormal, represents the method of choice for screening for squamous intraepithelial lesions (B-II). Annual anal cytology is recommended for PLWH of the GBMSM group (especially >35 years or advanced immunosuppression) and women with lower genital tract dysplasia (B-III).

- PLWH with liver cirrhosis and those with HBV infection and estimated risk of hepatocellular carcinoma greater than 0.2% per year should be screened by biannual liver ultrasound (A-I).

Neuropsychiatric alterations in HIV infection

- In PLWH, it is advisable to assess their emotional health, paying attention to coping strategies and stigma (A-III). In places where there is no free choice of a mental health specialist, it is recommended to study the case and authorize the requested changes of specialists.

- Validated scales such as the HADS can be used to screen for anxiety and depression at the time of diagnosis and on an annual or biennial basis (A-III).

- If depressive symptomatology is identified, suicide risk should be assessed using the MINI structured interview (B-II).

3.5 Particular aspects of the follow-up of women with HIV

Pregnancy

- Pregnancy is a criterion for an immediate referral from PC to HC. To avoid vertical transmission, all women with HIV should receive ART as early as possible, preferably before conception (A-II).

- The ART of choice should be triple therapy. Abacavir-lamivudine or TDF-emtricitabine combinations plus a third drug, which may be raltegravir, dolutegravir, or darunavir/ritonavir, are of choice. The choice will depend on the time of initiation (whether prior to conception or not), the history of resistance or intolerance, and the patient's preference (A-II).

- Intrapartum treatment with IV zidovudine is indicated if the plasma viral load is > 1000 copies/ml or unknown at delivery time (A-I).

- During delivery, cesarean section is indicated in women with confirmed or suspected viral load of more than 1000 copies/ml (A-II). It is recommended in women with a viral load between 50-1000 copies/ml, although each case should be personalized (B-III).

- In these circumstances, breastfeeding is not recommended (A-II).

Conception, contraception, menopause

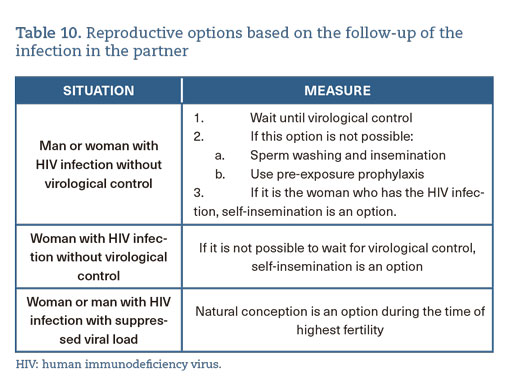

- In PLWH, family planning must be done in the best possible clinical situation, minimizing the risks for the woman, the couple, and the fetus, explaining the different reproductive options (A-II) (table 10).

- It is recommended to evaluate the age of onset of menopause, considering the symptoms associated with menopause, premature aging, and comorbidities. Hormone replacement therapy can be assessed with the same indications as in the general population (A-III).

- DEXA is advised in postmenopausal women with HIV infection (A-I).

3.6 Toxic habits

- It is recommended to ask about tobacco use at least once every two years and advise patients to quit smoking by providing help through specific intervention (A-I).

- Factors that negatively influence adherence to ART (alcohol and other drug abuse) should be addressed from PC and dealt with available resources (B-II).

- Refer PLWH with alcohol dependence (B-III), severe nicotine use disorder (A-III), or problematic drug use (including chemsex) to specialized Addiction Care. The comprehensive approach to chemsex users is detailed in the specific guidelines20.

- The treatment of choice for cannabis, cocaine, and MDMA abuse is psychotherapy and/or psychoeducation (B-II).

- Agreed-upon protocols for interdisciplinary work and referral between hospital emergency departments, PC, STI centers, HIV units, mental health and addiction resources, and community-based organizations should be designed and implemented (A-III).

- Preferential care centers for chemsex users should be identified in each city. A referral professional should be assigned to each user to follow up on the case and coordinate referrals between services (A-III).

4. Social aspects

How can the social determinants of vulnerability be approached?

- A gender approach should be incorporated, and all types of diversity (sexual, gender, class, functional, cognitive, age, and cultural) should be considered, along with the structural factors at the intersection of health and HIV, taking them into account when recording medical histories and while providing health care (A-II).

- Interventions must be adapted to the particularities of vulnerable PLWH (GBMSM, sex workers, transgender people, people with problematic drug use, and migrants), improving the interaction between socio-community services and PC/HC. (B-II)

Assessment of health-related quality of life

- Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in PLWH should be assessed to personalize and improve health care (B-II).

- The EQ-5D-5L instrument is one of the most commonly used tools for cost-efficiency calculations or comparisons with the general population. If the aim is to determine the degree to which different dimensions of HRQOL are affected, the WHOQOL-HIV-BREF is a reliable questionnaire with psychometric evidence for PLWH in Spain21,22 (B-III).

- HC typically has the most favorable settings to determine the HRQoL for PLWH, but the results should be shared with PC (B-III).

- Ideally, HRQoL should be recorded at the beginning of ART and annually before the follow-up consultation in HC (B-III).

Legal and ethical aspects. Confidentiality

- HIV testing should be informed and consented to by the patient. Healthcare facilities should ensure that the test is performed and the results are reported in a confidential manner (A-I).

- Training of healthcare and administrative personnel involved in the care of PLWH on privacy and confidentiality issues should be increased for all age ranges, considering the impact of gender, disability, and culture (A-III).

- The rights to privacy and data protection of PLWH should be guaranteed if there is no risk of transmission (see the original document where particular situations are detailed)1.

5. Shared teaching and research in HIV infection

- Regular teaching sessions should be agreed upon to generate shared knowledge regarding screening, management of HIV infection, comorbidities, and social, ethical, and legal aspects (A-II). Online formats and flexible schedules should be sought (B-III).

- The development of joint meetings between different healthcare settings should be encouraged concerning the shared care of PLWH and those at risk of acquiring HIV (A-III).

- Shared research between PC and HC should be promoted by creating multidisciplinary working groups on various topics (prevention, screening, connection to care, adherence to treatment, interactions, polypharmacy, management of comorbidities, quality of life, continuity of care) (B-III).

*MIEMBROS DEL GRUPO DE TRABAJO DE ATENCIÓN COMPARTIDA EN VIH DE LA SEMFYC Y DEL GRUPO DE ESTUDIO DEL SIDA DE GESIDA-SEIMC

- Ignacio Alastrué (semFYC). Centro de Información y Prevención del Sida y otras ITS de Valencia

- Juan E. Losa (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón. Madrid

- Nuria Orozco (semFYC). Centro de Salud Segorbe. Castellón

- María Jesús Pérez Elías (GeSIDA). Hospital Ramón y Cajal, IRYCIS. Madrid

- Jose L. Ramón (semFYC). Centro de Salud de Haro. La Rioja

- Cristina Agustí Benito (GeSIDA). CEEISCAT-CIBERESP. Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya

- Jésica Abadía (GeSIDA). Hospital Río Hortega. Valladolid

- Gaspar Alonso (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario de Getafe. Madrid

- Lara Arbizu (semFYC). Centro Salud Arnedo. La Rioja

- Pablo Bachiller (GeSIDA). Complejo Asistencial. Segovia

- Ignacio Barreira (semFYC). Hospital General Universitario. Valencia

- Josefina Belda (semFYC). Centro de Información y Prevención del Sida y otras ITS. Alicante

- Pilar Barrufet (GeSIDA). Hospital de Mataró. Barcelona

- Alfonso Cabello (GeSIDA). Fundación Jiménez Díaz. Madrid

- Arantxa Cabezas (GeSIDA). Asociación Bienestar y Desarrollo. Barcelona

- Lorena Caja (semFYC). Centro de Salud Fernando el Católico. Castellón

- Ricard Carrillo (semFYC). Centro de Salud La Florida Sud. Barcelona

- Miguel Cervero (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa. Madrid

- Javier de la Torre (GeSIDA). Hospital Costa del Sol. Marbella

- Ignacio de los Santos (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario de la Princesa. Madrid

- Alberto Díaz de Santiago (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro. Madrid

- Ana Díez (semFYC). Centro de Salud Puerta de Arnedo. La Rioja

- Francisco Fanjul (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Son Espases. Palma

- Mª Eugenia Flor (semFYC). Centro de Salud de Laguardia. Álava

- Juan Flores (GeSIDA). Hospital Arnau de Vilanova Valencia- Lliria

- Mª José Fuster (GeSIDA). Directora ejecutiva SEISIDA. Facultad de Psicología UNED

- Virginia Fuentes (semFYC). Centro de Salud Ruzafa. Valencia

- Carlos Galera (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Virgen Arrixaca. Murcia

- Mª José Galindo (GeSIDA). Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia. Valencia

- Lucio J. García-Fraile (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario de la Princesa. Madrid

- Alejandra Gimeno (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario de Torrejón. Madrid

- Cristina Gómez (GeSIDA). Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria. Málaga

- Jana Hernandez (GeSIDA). Hospital General de Villalba. Madrid

- Xabier Kortajarena (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Donostia

- Juan C. López (GeSIDA). Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid

- Juan Macías (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario de Valme. Sevilla

- Andrés Marco Mouriño (GeSIDA). Programa de Salud Penitenciaria. Institut Català de la Salut

- Luz Martín Carbonero (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid

- Javier Martínez Sanz (GeSIDA). Hospital Ramón y Cajal. Madrid

- Juanjo Mascort (semFYC). Centro de Salud La Florida Sud. Barcelona

- Aldana Menéndez (GeSIDA). Entidad ABD (asociación bienestar y desarrollo). Barcelona

- Dolores Merino (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez. Huelva

- Carolina Mir (semFYC). Centro de Salud Serrería 1. Valencia

- Raquel Monsalvo (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario del Tajo. Madrid

- Sara Nistal (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos. Madrid

- Nuria Orozco (semFYC). Centro de Salud Segorbe. Castellón

- Jesús Ortega (semFYC). Centro de Salud Navarrete. La Rioja

- Carmen Peinado (semFYC). Centro de Salud Nájera. La Rioja

- José L. Pérez (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina. Parla-Madrid

- Joseba Portu (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Araba Vitoria-Gasteiz

- Miguel A. Ramiro (GeSIDA). Clínica Legal, Universidad de Alcalá. Madrid

- Melchor Riera (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Son Espases. Palma de Mallorca

- Beatriz Rodríguez (semFYC). Centro Saúde Marín. Pontevedra

- Alberto Romero (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real. Cádiz

- Rafael Rubio García (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre. Instituto de Investigación i+12. Universidad Complutense. Madrid

- Pablo Ryan (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor. Madrid

- Jacinto Sánchez (GeSIDA). Complejo Asistencial Universitario. Palencia

- Yolanda Sánchez (semFYC). Centro de Salud Calahorra. La Rioja

- Tatia Santirso (semFYC). Unidad Docente Multiprofesional de Atención Familiar y Comunitaria. La Rioja

- José Sanz (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias. Alcalá de Henares. Madrid

- Regino Serrano (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario de Henares. Madrid

- María Velasco (GeSIDA). Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón. Madrid

- Mar Vera (GeSIDA). Centro Sanitario Sandoval. Madrid

- Cristina Zorzano (semFYC). Centro de Salud. Hormilla. La Rioja

_1708003063.jpg)